A story of courage, vision, and sacrifice — discover how Kruger’s first rangers and conservation pioneers saved Africa’s wilderness and shaped the park we know today.

Bushveld Battlefields: The Great South African War Echoes Around the Park

Discover echoes of The Great South African War in the Kruger Lowveld. From Komatipoort to Barberton, the bushveld still remembers its wartime past.

The Lowveld is a place of contrasts. Today, it is celebrated for its elephants trudging across riverbeds, its hornbills calling from acacia perches, and the endless horizons of Kruger National Park. Yet not so long ago—barely a century—the same bushveld carried the smoke of campfires, the rumble of gun carriages, and the uneasy silence of men at war.

The Great South African War (1899–1902), one of the most defining conflicts in South African history, unfolded not only on the open battlefields of the Free State and Natal, but also here on the edges of Kruger and Marloth Park. Where we now come to seek wilderness, soldiers once dug trenches, manned outposts, and guarded vital railways. The veld remembers, even if it has since healed.

The Lowveld as a Frontier

At the dawn of the 20th century, this was a frontier in every sense. The Delagoa Bay railway line, threading through Komatipoort to the Mozambican coast, was a lifeline for the Boer republics. Guns, ammunition, and supplies came rattling down the line; hope itself seemed tied to the iron tracks.

For the British, the Lowveld was a key to cutting that line. For the Boers, it was the last open door to the world. And so Komatipoort became both a strategic prize and a place of endings. In 1900, thousands of Boer fighters laid down arms here and crossed into Portuguese East Africa, their war over. Today, it is a bustling border town, but beneath the sound of taxis and trains lies the echo of uncertainty that once gripped its dusty streets.

Steinaecker’s Horse: Rangers of the Bush

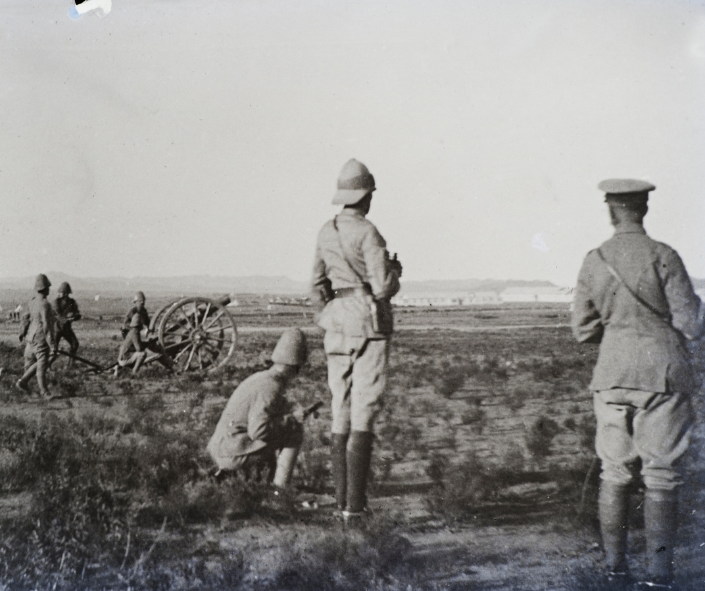

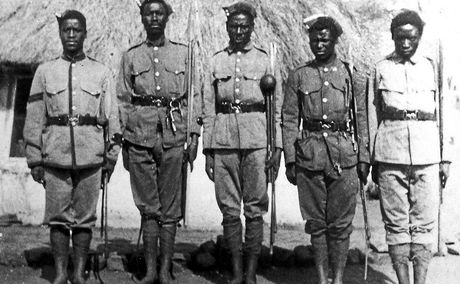

Few stories from this region are as compelling as that of Steinaecker’s Horse. This irregular British unit—an unlikely mix of adventurers, locals, and opportunists—patrolled the frontier across what is now southern Kruger National Park.

They built outposts at strategic points: Sabi Bridge (today’s Skukuza), Gaza Gray near Lower Sabie, and sites along the Lebombo ridges. Their job was not glamorous—hours of lonely watch, malaria and fever as constant enemies, lions circling at night, and the occasional skirmish with Boer commandos slipping across the border.

Most traces of their presence are gone, absorbed back into the bush. A few artefacts remain—spent cartridges, rusted tins, old stone outlines—but the most powerful legacy is the idea itself: men holding a military line in the very wilderness that now draws travellers for peace and discovery.

Blockhouses and the Iron Lines of Strategy

The Great South African War was, in many ways, a war of logistics. The British understood that whoever held the railways held the future. To guard these lifelines, they built chains of blockhouses—stout little forts of stone or corrugated iron, spaced within sight of each other.

The line from Komatipoort to Wonderfontein, nearly 280 kilometres long, became South Africa’s longest fortified railway. Imagine the scene: soldiers posted in these squat towers, scanning the veld through rifle slits while, beyond the fence, elephants and antelope carried on as they had for millennia.

Today, most blockhouses have crumbled or been dismantled, yet the landscape itself still tells their story. Koppies became lookouts, river crossings became choke points, and bridges were forever vulnerable. Where you see terrain, they saw tactics.

Barberton: Gold and Guerrilla Shadows

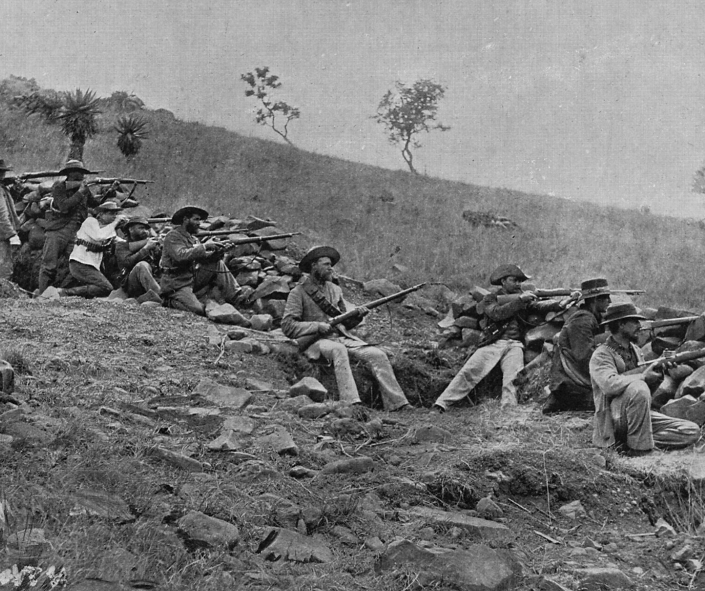

To the west, the Barberton hills carried their own war story. This was a land already rich in tales—gold rushes, geological wonders, the ancient Barberton Greenstone Belt. But during the guerrilla phase of The Great South African War, the valleys also sheltered Boer fighters.

Commandos used the rugged folds of these mountains to evade patrols, staging sudden raids before vanishing again into the greenstone labyrinth. Barberton’s streets, better known for miners and prospectors, were also patrolled by Town Guards, wary of the next strike.

The town has since grown into a heritage hub, remembered more for gold than gunfire—but for those who listen closely, the whispers of war remain part of its fabric.

Why This History Still Matters

Most travellers come to Marloth Park and Kruger to encounter wildness—to see lions, elephants, or perhaps the elusive martial eagle. But understanding the human history of the Lowveld adds another dimension to every drive, every walk, every evening around the fire.

The same koppies where you pause to admire a sunset once bristled with armed lookouts. The same rivers where elephants gather at dusk once carried weary fighters seeking refuge. The Lowveld’s genius is its ability to absorb both war and wilderness, and to heal until only the attentive eye can tell the difference.

At Needles Lodge, set quietly among the bush of Marloth Park, this layered history enriches the safari experience. Guests come for wildlife, but many leave with a sense of connection to the deeper stories of the land: that this region has always been contested, always valued, always alive with meaning.

Bushveld Memory

Unlike the monumental battlefields of Ladysmith or Magersfontein, The Great South African War in the Lowveldleaves only subtle traces. A rusted railway sleeper, a forgotten place name, a low wall in the grass. Nature has reclaimed almost everything, as it always does.

And yet, memory persists. The bushveld itself is a living archive. Just as we learn to read spoor in the sand or the alarm call of an impala, we can learn to read the faint outlines of human history here.

The gift of the Lowveld is that it offers both: the thrill of the present—the elephant crashing through thickets, the leopard melting into dusk—and the echo of the past, still woven into the land’s heartbeat.

Further Reading

Planning a Kruger National Park safari? Explore the pros and cons of self-drive vs. guided game drives, and discover which safari experience is best for you!

Cultural tours at Needles Lodge offer travelers a deep immersion into the local traditions and lifestyles of nearby communities, including full-day excursions to Eswatini, Maputo, and the Lowveld Escarpment.

The baobab tree, an African icon, symbolizes resilience and life, deeply rooted in African culture and ecosystems. Revered in folklore and vital in maintaining ecological balance, it offers shelter and sustenance to diverse species and serves as a communal hub, with its uses ranging from medicine to crafts. Eco-tourism, particularly in areas like Kruger National Park, plays a key role in its conservation, raising awareness and funds to protect this majestic tree,...

Share This Post